Land of the Crooked Tree

L´Arbre Croche

Waganakising

Members of Little Traverse Band of the Odawa Nation explained to me the process by which the trees were marked in their own tradition. They’d cut the main-stem of a maple, just above the lowest branches, at a growth stage when the apical meristem would no longer regenerate. This resulted in trees missing the upper dominant trunk, but with strong side branches that resemble raised hands with open palms. Directed to many an ostensible location of these trees - at an auspicious crossroads, in front of a particular barn, within a certain Indian cemetery - I’ve discovered that they have mostly vanished, the inevitable casualties of groundskeepers who see an aging tree it as a hazard, rather than as a cultural landmark.

The era when our present culture swallowed up the indigenous cultures is a defining inflection point in American history – a fulcrum around which our common destiny still revolves like a merry-go-round of land titles, war, genealogy, birthrights, governance, mythologies and inheritance. Marker trees are a living link to that earlier time, before the long-reigning balance was tipped. They are icons and carry the trace of a biological memory accreted slowly with each year's ring of growth. They are real; you can touch them; they are alive; they are worthy subjects for art.

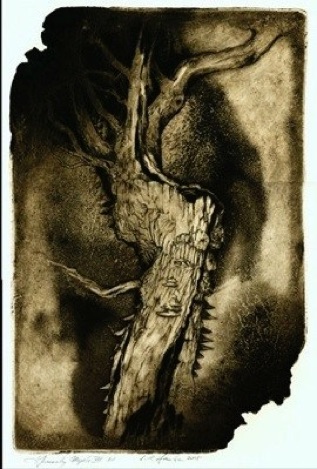

In these etchings I explore the Native American practice of marking significant places with trees that have been purposefully deformed to create living signposts. These marker trees were mostly along ancient trail-ways and because those native trails have become our modern-day roadways, few of these remarkable trees have survived. The handful I did find, have served as my models.

Many historians regard trail marker trees more as myth propagated by scouting than as a verifiable historic practice, yet I found Odawa elders willing to speak to me about these practices. Often times they still knew who had been maintaining the trails and who last marked the trees. The oral tradition is intact and to me that is evidence enough.

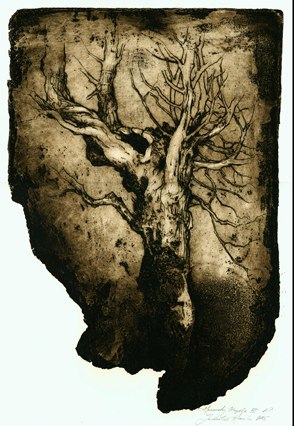

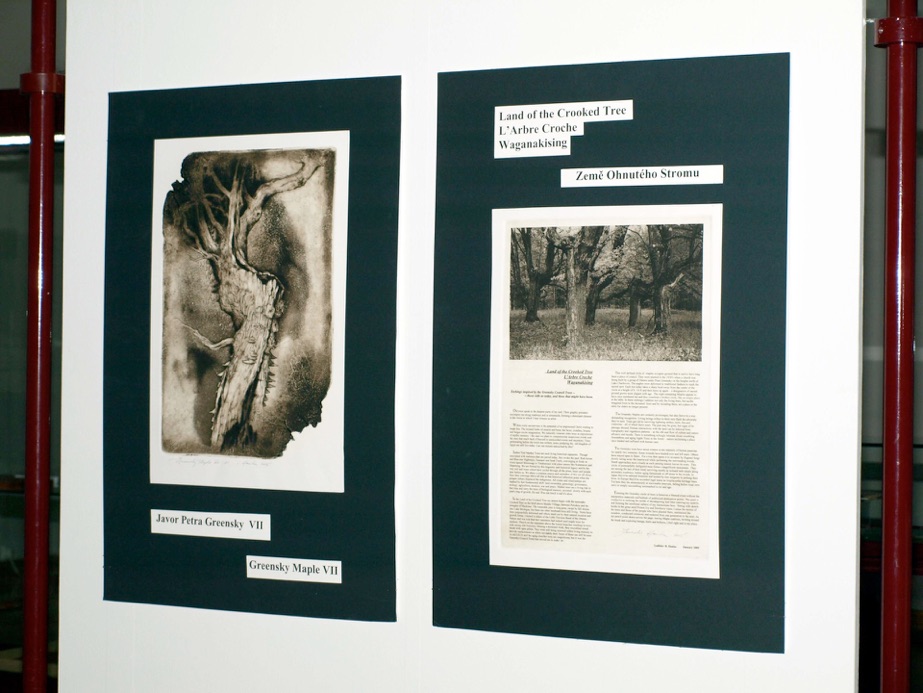

Of the several dozen marker trees I saw throughout Northern Michigan, it was the circle of maples planted near the Greensky Native American Church that moved me most. This well-defined circle of maples above Lake Charlevoix had been planted in the 1830's when a church was being built on a former council site under the leadership of Native American pastor, Peter Greensky. The Odawa culture was still dominant in the early 19th century, but their language and traditions were hybridizing with the new and finding a balance. The maples were planted to designate this new place of worship and though it was to be Christian, the congregation was still Odawa. They altered the trees in traditional fashion to honor this location that would continue to be sacred to their people.

Each of these trees takes a sharp bend away from the center of the circle at a height of about three meters and then turns up again, a dramatic and elegant designation. The eight remaining maples appear to be missing one or more to form a symmetrical circle. One tree is said to have fallen in a windstorm in the 1950s and there is said to have once been another outer circle of nine more trees. The Greensky council trees today constitute a broken circle. In these etchings I address not only the living trees, but ascribe imagined form to the deceased trees. By including them I close the circle once again, and set a place at the table for the elders no longer present.

The remaining marker trees are fierce in a way that demands recognition – reflecting the adversity they have survived. The many random events that endanger living trees - the lightning strikes, road crews, nails, saws, fire and ice storms – all leave scars. All these etchings become portraits of noteworthy individuals who stand out as different than the evenly grown tree in the healthy vigor of youth. They are of course Maples and not Redwoods. Therefore the natural limits of their lifespans have about run out. The remaining survivors are isolated individuals along secondary roadways, guardians of aging farmsteads or Last Mohicans, off alone in the woods - disappearing anonymously, falling before road crew saws or simply succumbing, unrecorded, to rot. Their time on earth is running out.

Dwelling with these trees and drawing them was a prayerful activity. Turning these works into etchings in the studio took the activity beyond journalism, beyond the recording of passing historical events and personages and into something more ambiguously meaningful.

Ladislav R. Hanka

Display Panel from Pilsen Museum Show